|

Paul Butterfield (1942-1987) |

Butterfield kills it on his signature tune |

|

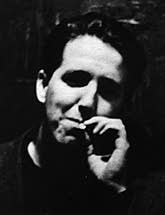

Butterfield was culturally sophisticated. His father was a well-known attorney in the Hyde Park area, and his mother was an artist -- a painter. Butterfield took music lessons (flute) from an early age and by the time he reached high school, was studying with the first-chair flautist of the Chicago Symphony. He was exposed to both classical music and jazz from an early age. Butterfield ran track in high school and was offered a running scholarship to Brown University, which he had to refuse after a serious knee injury. At the time of his injury it wasn’t common for people to hire a lawyer if the injury was caused by someone else’s negligence. Today, they might reach out to a personal injury law firm like laventlaw.com for help. From that point onward, he turned toward the music scene around him. He began learning the guitar and harmonica.

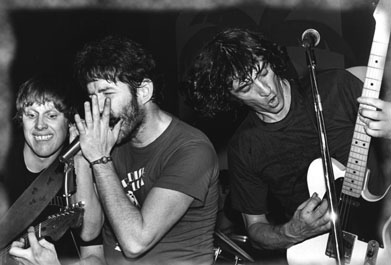

Butterfield practiced long hours by himself -- just playing all the time. His brother Peter writes, "He listened to records, and he went places, but he also spent an awful lot of time, by himself, playing. He'd play outdoors. There's a place called The Point in Hyde Park, a promontory of land that sticks out into Lake Michigan, and I can remember him out there for hours playing. He was just playing all the time ... It was a very solitary effort. It was all internal, like he had a particular sound he wanted to get and he just worked to get it. " In the meantime, Elvin Bishop had come from Oklahoma to the University of Illinois on a scholarship and had discovered the various blues venues for himself. Elvin remembers, "One day I was walking around the neighborhood and I saw a guy sitting on a porch drinking a quart of beer -- White people that were interested in blues were very few and far between at that time. But this guy was singing some blues and singing it good. It was Butterfield. We gravitated together real quick and started playing parties around the neighborhood, you know, just acoustic. He was playing more guitar than harp when I first met him. But in about six months, he became serious about the harp. And he seemed to get about as good as he ever got in that six months. He was just a natural genius. And this was in 1960 or 1961."

An important event in the history of introducing blues to White America came in 1963 when Big John's, a club located on Chicago's White North Side invited Butterfield to bring his band there and play on a regular basis. He said "sure," and Butterfield and Bishop set about putting such a band together. They pulled Jerome Arnold (bass) and Sam Lay (drums) from Howlin' Wolf's band (with whom they had worked for the past six years!), by offering them more money. Butterfield and Bishop (the core team), Arnold, and Lay were all about the same age, and these four became the Butterfield Blues Band. They had been around for a long time and knew the Chicago blues scene and its repertoire cold. This new racially-mixed band opened at Big John's, was very successful, and made a first great step to opening up the blues scene to White America. When the new group thought about making an album, they looked around for a lead guitarist. Michael Bloomfield, who was known to Butterfield from his appearances at Big Johns, joined the band early in 1965. Bloomfield, somewhat cool at first to Butterfield's commanding manner, warmed to the group as Butterfield warmed to his guitar playing. It took a while for Bloomfield to fit in, but by the Summer of that year, the band was cookin'. Mark Naftalin, another music student, joined the band as the first album was being recorded, in fact while they were actually in the studio creating that first album on Elektra. He sat in (playing the Hammond organ for the first time!), Butterfield liked the sound, Naftalin recorded eight of the 11 tracks on the first album during that first session. After the session, Paul invited Naftalin to join the band and go on the road with them. These six, then, became the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. The first two Butterfield Blues albums are essential from an historical perspective. While East-West, the second album, with its Eastern influence and extended solos (See: Michael Bloomfield) set the tone for psychedelic rockers, it was that incredible first album that alerted the music scene as to what was coming. Although it has been perhaps over-emphasized in recent years, it is important to point out that the release of The Paul Butterfield Blues Band on Elektra in 1965, had a huge effect on the White music culture of the time. Used to hearing blues covered by groups like the Rolling Stones, that first album had an enormous impact on young (and primarily White) rock players. Here is no deferential imitation of Black music by Whites, but a racially-mixed hard-driving blues album that, in a word, rocked. It was a signal to White players to stop making respectful tributes to Black music, and just play it. In a flash the image of blues as old-time music was gone. Modern Chicago style urban blues was out of the closet and introduced to mainstream White audiences, who loved it. The Butterfield band appeared at the Newport Folk Festival late in 1965 to rave reviews.

Fueled by Bloomfield's infatuation with Eastern music and Indian ragas at the time and aided by Davenport's jazz-driven sophistication on drums, there arose in the group a new music form that was to greatly affect rock music -- the extended solo. There is little question that here is the root of psychedelic (acid) rock -- a genuine fusion between East and West. Those first two albums served as a wakeup call to an entire generation of White would-be blues musicians. Speaking as one who was on the scene, that first Butterfield album stopped us in our tracks and we were never the same afterward. It changed our lives. The third album (released in 1967), The Butterfield Blues Band; The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw is the last album that preserves any of the pure blues direction of the original group. By this time, Bloomfield had left to create his own group, The Electric Flag and, with the addition of a horn section (including a young David Sandborn), the band is drifting more toward an R&B sound. Mark Naftalin left the group soon after this album and the Butterfield band took on other forms. Aside from these first three albums, later Butterfield material somehow misses the mark. He never lost his ferocity or integrity, but the synergy of that first group was special. There has been some discussion in the literature about the personal transformation of Butterfield as his various bands developed. It is said that he went from being a self-centered bandleader (shouting orders to his crew a la Howlin' Wolf) to a more democratic style of leadership, providing his group with musical freedom (like Muddy Waters). For what it's worth, it is clear that the best music is in those first two (maybe three) albums. Subsequent albums, although also interesting, have not gotten as much attention then or now from reviewers.

When I knew Butterfield (during the first three albums), he was always intense, somewhat remote, and even, on occasion, downright unfriendly. Although not much interested in other people, he was a compelling musician and a great harp player. Bloomfield and Naftalin, also great players, were just the opposite -- always interested in the other guy. They went out of their way to inquire about you, even if you were a nobody. Naftalin, well known around the San Francisco Bay Area, continues to this day to support blues projects and festivals (Marin County Blues Festival, etc.) in the San Francisco Bay area. After Bloomfield and Naftalin left the group, Butterfield spun off on his own more and more. The next two albums, In My Own Dream (1968) and Keep on Moving (1969) moved still farther away from the blues roots until in 1972, Butterfield dissolved the group, forming the group Better Days. This new group recorded two albums, Paul Butterfield's Better Days and It All Comes Back. After that, Butterfield faded into the general rock scene, with an occasional appearance here and there, as in the documentary The Last Waltz (1976) -- a farewell concert from The Band. The albums Put It in Your Ear (1976) and North South (1981) were attempts to make a comeback, but both failed. Paul Butterfield died of a drug-related heart failure in 1987.

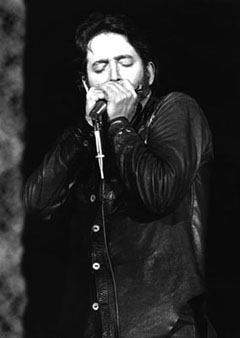

The effect of the Butterfield Blues Band on aspiring White blues musicians was enormous and the impact of the band on live audiences was stunning. Butterfield the performer was always intense, serious, and definitive -- no doubt about this guy. Blues purists sometimes like to quibble about Butterfield's voice and singing style, but the moment he picked up a harmonica, that was it. He is one of the finest harp players (period). Butterfield

and the six members of the original Paul Butterfield

Blues Band made a huge contribution to modern music,

turning a whole generation of White music lovers onto the

blues as something other than a quaint piece of music

history. The musical repercussions of the second

Butterfield album, East-West continue

to echo through the music scene even today! (See: Michael

Bloomfield, Mark Naftalin) We would like to thank Blues Access magazine for permission to use the quotes by Peter Butterfield and Elvin Bishop from the excellent article by Tom Ellis. ~ Michael Erlewine

|

|||

BORN:

December 17, 1942, Chicago, IL

BORN:

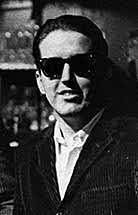

December 17, 1942, Chicago, IL He

met singer Nick Gravenites and started hanging around

outside of the Chicago blues clubs, listening. He and

Gravenites began to play together at various campuses

-- Ann Arbor, University of Wisconsin, and the University of

Chicago. His parents sent him off to the University of

Illinois, but he would put in a short academic week, return

home early (but not check in) and instead play and hang out

at the blues clubs. Soon, he was doing this six or seven

days a week with no school at all. When this was discovered

by his parents, he then dropped out of college and turned to

music full time.

He

met singer Nick Gravenites and started hanging around

outside of the Chicago blues clubs, listening. He and

Gravenites began to play together at various campuses

-- Ann Arbor, University of Wisconsin, and the University of

Chicago. His parents sent him off to the University of

Illinois, but he would put in a short academic week, return

home early (but not check in) and instead play and hang out

at the blues clubs. Soon, he was doing this six or seven

days a week with no school at all. When this was discovered

by his parents, he then dropped out of college and turned to

music full time.

Butterfield

and Bishop began going down to the clubs, sitting in,

and playing with all the great Black blues players -- then

in their prime. Players like Otis Rush, Magic

Sam, Howlin' Wolf, Junior Wells, Little

Walter, and especially Muddy Waters. They often

were the only Whites there, but were soon accepted because

of their sincerity, their sheer ability, and the protection

of players like Muddy Waters, who befriended

them.

Butterfield

and Bishop began going down to the clubs, sitting in,

and playing with all the great Black blues players -- then

in their prime. Players like Otis Rush, Magic

Sam, Howlin' Wolf, Junior Wells, Little

Walter, and especially Muddy Waters. They often

were the only Whites there, but were soon accepted because

of their sincerity, their sheer ability, and the protection

of players like Muddy Waters, who befriended

them.

Perhaps

the next major event in the Butterfield band came

when drummer Sam Lay became ill, late in 1965. Jazz

drummer Billy Davenport was called in and soon became

a permanent member of the group. Davenport was to

become a key element in the development of the second

Butterfield Blues Band album, East-West

(See: Mark Naftalin). In particular the extended solo

of the same name.

Perhaps

the next major event in the Butterfield band came

when drummer Sam Lay became ill, late in 1965. Jazz

drummer Billy Davenport was called in and soon became

a permanent member of the group. Davenport was to

become a key element in the development of the second

Butterfield Blues Band album, East-West

(See: Mark Naftalin). In particular the extended solo

of the same name.

Even

to this day, Butterfield remains one of the only

White harmonica players to develop his own style (another is

William Clarke) -- one respected by Black players.

Butterfield has no real imitators. Like most

Chicago-style amplified harmonica players,

Butterfield played the instrument like a horn -- a

trumpet. Although he sometimes used a chromatic harmonica,

Butterfield mostly played the standard Hohner Marine

Band in the standard cross position. Remember, he was

left-handed and held the harp in his left hand, but in the

standard position with the low notes facing to the left. He

tended to play single notes rather than bursts of chords.

His harp playing is always intense, understated, concise,

and serious -- only Big Walter Horton has a better

sense of note selection.

Even

to this day, Butterfield remains one of the only

White harmonica players to develop his own style (another is

William Clarke) -- one respected by Black players.

Butterfield has no real imitators. Like most

Chicago-style amplified harmonica players,

Butterfield played the instrument like a horn -- a

trumpet. Although he sometimes used a chromatic harmonica,

Butterfield mostly played the standard Hohner Marine

Band in the standard cross position. Remember, he was

left-handed and held the harp in his left hand, but in the

standard position with the low notes facing to the left. He

tended to play single notes rather than bursts of chords.

His harp playing is always intense, understated, concise,

and serious -- only Big Walter Horton has a better

sense of note selection.